THE PERSONAL STORM OF CONNEE BOSWELL

By Cort Vitty © 2012

(From Radio Recall, February 2012)

A sedan approached the newsstand at 72nd and Broadway in New York. The passenger instructed her driver to pull over and wait. It seemed like hours passed before a young man on crutches slowly shuffled toward the stand; his legs were withered by the crippling affect of polio. From the back seat, singer Connie Boswell immediately understood why columnist Walter Winchell contacted her to arrange the meeting; she too was a victim of polio -- unable to walk since the age of 3.

No one knows what Connie specifically said to the newsboy that day, but undoubtedly the conversation centered on living with polio. Connie likely imparted the early advice given by her mother, Meldania Forre Boswell: "Connie, you'll never walk or dance. But these things are unimportant. What IS important is to use your brain. Develop your own talents and you'll have just as much pleasure out of life as anyone else."

The polio virus dates back to ancient times. Throughout recorded history, outbreaks of epidemic proportion have periodically occurred without warning. Sadly, small children and young adults were stricken most often by the debilitating paralysis. Thanks to the mid 20th century introduction of an oral vaccine, the disease is rare today and close to eradication.

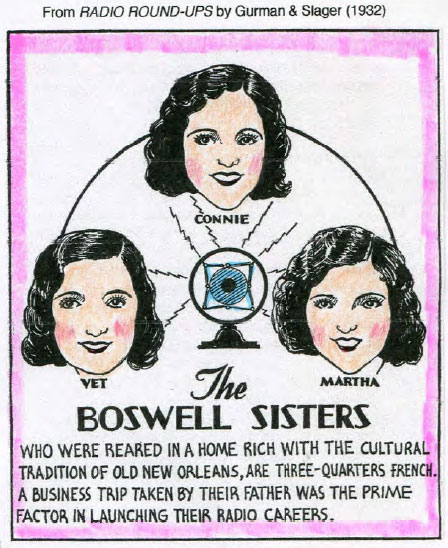

The Boswell family moved to New Orleans from Missouri in 1914, when patriarch Alfred Clyde accepted a management position with a yeast company. The family consisted of oldest son Clyde Jr. (1900-1918), along with daughters, Martha (1905-1958), Connie (1907-1976) and (Vet) Helvetia (1911-1988). Meldania instilled an appreciation of music in her daughters and viewed it as a particular opportunity for Connie. A classically trained teacher was hired to provide lessons for the girls. Martha learned to play piano; Connie mastered the cello, saxophone and guitar, while Vet became proficient with the violin and banjo.

"My mother never babied me," explained Connie. "She insisted that my sisters and playmates treat me, just as any other youngster. She never said: 'Now be careful of poor Connie; remember she can't walk. She sent me to public schools and insisted I fight my own battles." The family employed three local black women to help with domestic chores. The ladies befriended the girls and became part of the family; they'd happily sing while working and introduced the sisters to the sound of blues and spirituals.

Alfred's brother married Meldania's sister and they'd delight the girls by singing Stephan Foster tunes as a quartet. According to Boswell biographer David McCain, the sisters liked the impromptu harmony so much; they later unsuccessfully "searched for a fourth voice to form a quartet." Instead, they learned to sound like a quartet by varying their vocal styles.

The sisters visited black churches in the French Quarter to hear gospel music. On these trips, Martha and Vet would interlock their hands to carry Connie. The girls began playfully adding a gospel style tempo as they practiced classical music. This improvisation of style would eventually make its way into their early public performances.

By 1919, the girls were appearing at concerts and vaudeville shows. They were so young; their school principal had to grant permission for them to accept their first professional job. At a talent contest in 1922, a canceled act presented an opportunity for the sisters to perform their unique arrangements, complete with scatting and key changes. Connie provided the vocals, with harmony added by Martha and Vet. The sisters became an immediate hit, embarking them on a cross-country Vaudeville tour. In 1928, they ended up in San Francisco, meeting a young hotel clerk named Harry Leedy, who would ultimately become their manager.

Depression era times were tough on the road, as Connie related to record producer Michael Brooks: "I remember a pretty grueling weekend stint at a movie-house. We wound up the date and Martha seemed very quiet. She showed me the check; it was for $3.00." They accepted an offer to perform 5 nights a week on California Melodies, heard over KHJ radio in Los Angeles. The sisters next left for KGO (in San Francisco) the NBC flagship affiliate on the west coast, where "their jazz-infused harmony took the world by storm on network radio.â€"

The Boswell sisters originally met Bing Crosby when he performed with Paul Whiteman's Rhythm Boys. They later appeared with Bing in The Big Broadcast of 1932. The sisters moved to the Chesterfield Hour in 1933, and again teamed with Bing on his radio show in 1934. The Boswell's sang on many top network shows, including The California Hour and Kraft Music Hall. The sisters performed at Buckingham Palace in 1935, as part of a European tour.

Connie and manager Harry Leedy were married in New York on December 14th 1935. Since all three Bozzies married that year, new brides Martha and Vet decided to retire, leaving Connie to embark on a solo career. It was a move that would raise her to new heights of popularity and musical innovation, prompting no less than Irving Berlin to call her "the best ballad singer in the business." As a highly sought after radio personality, Connie continued to appear with Bing Crosby and was regularly featured on such popular shows as Camel Caravan, Good News and The Ken Murray Show. Film work included Artists & Models in 1937.

During the peak years of her career, Connie hired (then) unknown musicians such as Artie Shaw, Benny Goodman and Jimmy Dorsey, to provide instrumentation for her recordings. During one session, all three added a clarinet background. Connie also gave Glenn Miller his first opportunity to arrange.

The onset of WW II meant touring and signing autographs for troops. The loss of dexterity from the lingering affect of polio made it difficult to dot the "i" in her name, making Connee a more practical alternative; by 1942, she legally changed the spelling. She volunteered to perform overseas, but she remained stateside due to her handicap, which restricted travel. Her V-Disc recordings and song dedications on Command Performance were favorites with the troops.

Connee's live performances had an innate power to make people take a closer look at their own lives. The sight of a cheerful young woman being wheeled on stage, propped atop an elevated platform with a long gown covering her crippled legs, was sometimes too much for an audience to handle. But Connee, with her pleasant temperament, "which was as breezy as the beat of her music" weathered well her own personal storm.

Connee appeared in the 1941 film, Kiss the Boys Goodbye. On radio, she hosted her own Connee Boswell Show in 1944. In 1946, she appeared in the film Swing Parade and sang "Stormy Weather," which had become one of her signature songs. Syndicated author Elsie Robinson described Connee singing Stormy Weather in a Listen World column: "A roar greeted her. Here was valiant Connie Boswell, beloved by the radio world; tears on her face, hands trembling; singing Stormy Weather; and in that song was the hurt of humanity; in every heart that heard her."

Television emerged in the early 1950s and Connee made regular appearances with Ed Sullivan and Perry Como. In 1955, she was a guest on Person to Person, hosted by Edward R. Murrow. What did Connee think of rock 'n' roll? "Believe it or not, I like Elvis Presley - So sue me. The basic beat of rock 'n' roll isn't too far from the jazz of the old days." A sapient Connee added: "Nothing will ever destroy jazz. It will be around for a long time."

In 1959, a television version of Pete Kelly's Blues premiered and Connee signed on to play lounge singer Savannah Brown. The drama, set in the 1920s, was originally a radio entry in 1951. UPI Hollywood interviewed Connee before production and she remarked: "There's a lot of nostalgia for me about the '20s. My sisters and I were just getting our start as the old Boswell Sisters act." Connee continued: "I'll be singing the way I always have. It's natural for me to belt out songs as they come to my mind, and I never sing a song the same way twice."

Connee worked tirelessly on behalf of the March of Dimes and regularly visited hospitalized children during her travels around the country; the visits were always unannounced and never publicized. Despite her handicap, Connie believed regular exercise was essential to good health and maintaining her throaty contralto voice. A stationary bike and rowing machine were standard equipment on road trips. She enjoyed baseball, football, horse racing and hockey.

In March of 1955, Connee was one of 66 passengers aboard a flight from Los Angeles to New York. The DC-7 developed engine trouble and was forced to make an emergency landing in Chicago. Connee noting the tension among nervous passengers impetuously started singing "Coming in on a Wing and a Prayer" to comfort frazzled nerves; she was later praised for her heroic action.

A planned visit to Chicago took place a couple of months later when Connee attended the 50th anniversary convention of Rotary International. A caption below the entertainer's photo in The Rotarian magazine stated: "Singer Connee Boswell stars too in the book of personal courage." The eradication of polio would later become Rotary's signature project.

A devoted couple, Connee and Harry Leedy were married almost 40 years, when Harry quietly passed away in his sleep on New Years Day 1975. Early in 1976, Connee became ill and was diagnosed with stomach cancer. She underwent surgery in February and started chemotherapy. By October, she requested that all treatment stop to "let me die in peace and dignity." She passed away at Mt. Sinai Hospital in New York on October 11th 1976, with her sister Vet by her side.

News of her passing brought accolades from the world of entertainment. Bing Crosby called her "a great lady with boundless courage and divine talent." Patty Andrews added: "If it weren't for the Boswell Sisters, there would never have been the Andrews Sisters." Ella Fitzgerald stated: "When I was young I wanted to sing like Connie Boswell." Frank Sinatra called her "the most widely imitated singer of all time."

SOURCES:

Baltimore Sun; Biograph Records; Chicago Daily Tribune; Discovering Great Singers of Classic Pop; New York Times; Radio Guide; San Antonio Light; The Rotarian; Washington Post; www.bozzies.org

|